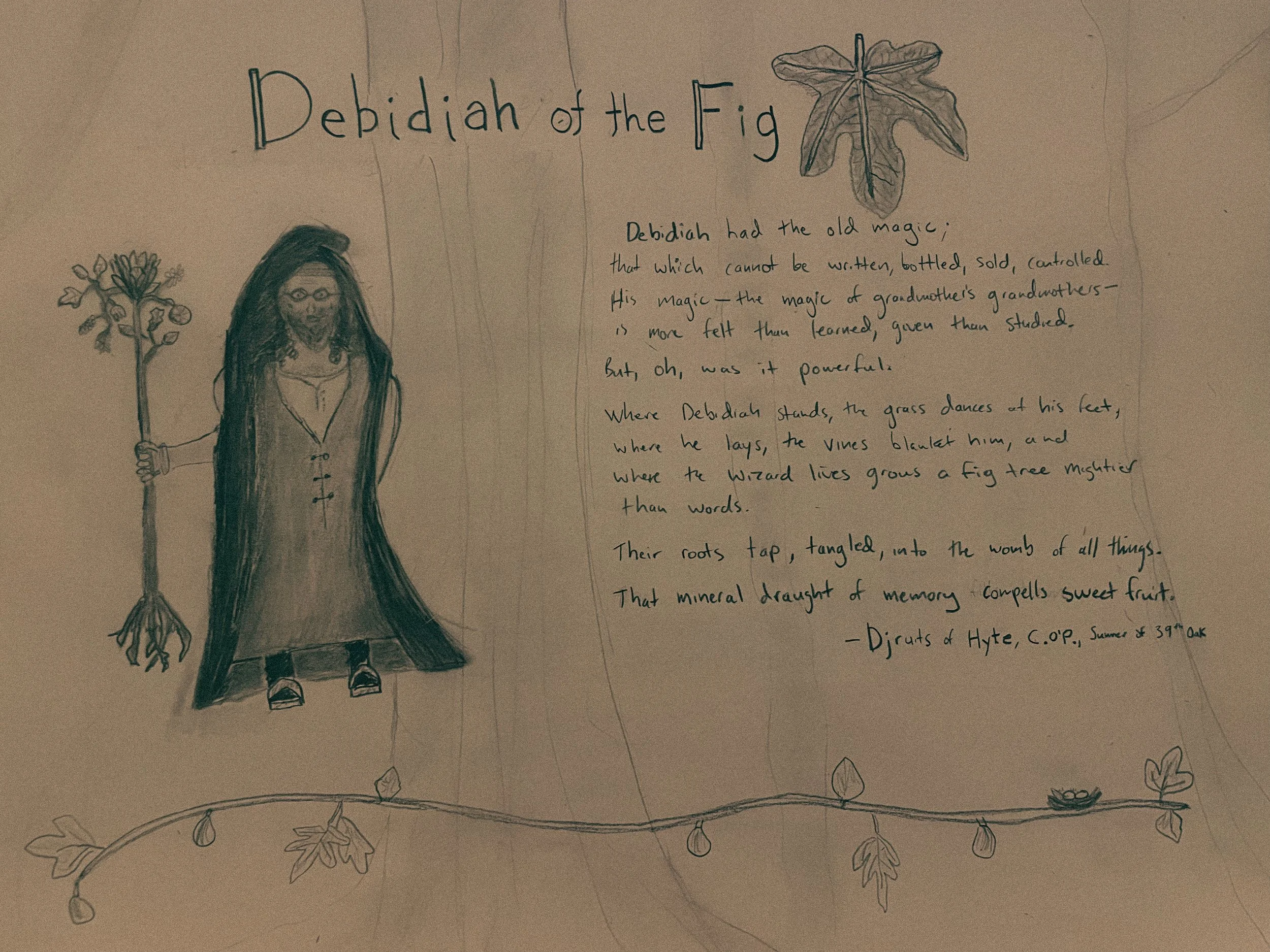

Debidiah of the Fig

You can see her from two hard days away; a sage green sunrise amidst the rolling mountain tops that are alone her rivals. Resolute as they are innumerable, her arms, long extended, have dug deep into the ground as if to tap at the very heart of the world. Like great pillars of stone her aerial roots and branches buttress her dome, so dense and broad that it shades the entire mountain on blazing days when even the moon glows hot. Under that cool canopy in a chorus of lichen, worms, piercing roots, and centuries, the rock became pliant soil that nourished a kaleidoscope of life. Ferns, mosses, orchid, vines, and woodbeard grew in all the cracks between branches and half-crushed boulders. She became a home for generations of parrots, flying foxes, gibbons, squirrels, and wasps that thrived on her bountiful fruit and shade. In the mornings the sea fog shroud would roll in like incense burning, swirling through the trunks and branches. Over many years, fog-salt crystals would form on the gray trunks in a glossy sheen for the licking of wandering goats and elephants. Were she but a building, she would be as beautiful and formidable as any palace, city, or fortress of man in Hyte, and as old.

The Fig, whose name was Mahalak, was once a place of pilgrims, dance, and sacred rites. But as man gave way to the intoxication of power and dominion, they came to fear and resent her. Kings and warlords alike, made small by her legions of leaves like verdant tridents, stopped visiting and made no offerings for generations and her memory was forgotten by those who lived outside of the Shrouded Forest.

And so Mahalak sat strangling, devouring, loving the mountain on which she was sown by way unknown. As child to mother, the tree accepted the generosity of the rock until the heir had eclipsed the parent in fortitude and vigor, and set her sights onward. She was the grandest cathedral-being in Hyte. Under her canopy ten thousand monks could have lived and worshiped, but now there is only one: the acolyte Debidiah. And the boy adventurer, Choi o’Puyo, would soon meet them.

***

It had been a week since Choi had emerged from the Spine and into the jungle. His leg pained him worse by the day, but he had no hope for rest in the shrouded land. The stories told Choi that if he stayed in that misty tangle for too long that his mind would leave him, and he felt it too. He would hike until he reached the wretched sea where he could chart a true course Northerly towards his destination. But Choi did not know how to reach the sea; the woods were too thick and the night sky was foreign to him. He could scarcely trust the sun which appeared only capriciously between rain showers and fog banks.

Choi was lost and disoriented as he lumbered through the bush. As he wandered, he would hear branches crack and soft whispers on the wind, but whenever he turned his head to investigate he would see only a strange bright bird or lizard in a wall of green foliage. He felt eyes on him from the shadows often. Choi did not fear the beasts in the pall--he had already bested a ghost cat of the mountains, and now wore its pelt as a cloak. But Choi did fear the gaze in the mist; it felt intelligent and increasingly interested in him.

He begged: “I am Choi o’Puyo! I have come through snow and sand on wing, hoof, foot, and landsail. I mean just to pass through your woods, dear gentle quiet ones. I seek the flat lands of Ornal, bearing a message of peace for the Lord King in his castle at the end of the world. I come from a small village in the shadow of the Holy Mountain. I’ve heard tales of the mistfolk, that you live with the trees like lovers and grow in the sun. I should like to meet face to face, as I mean no harm.” His pleadings and explanations were always to no avail.

Choi’s sleep was light and his dreams were feverish under the thick fur pelt. Hunger, pain, and paranoia weighed on him in sleepfulness and wakefulness, which blurred increasingly. As Choi’s hope faded, he came upon a clearing on a hilltop. The fog had been burned off by the sun and he could survey the landscape. In all directions he could see only rolling hills blanketed in emerald and gossamer. To the East, he could see the faint outlines of the mighty peaks of the Spine. He knew the sea was to the West and should try to go that way, though it was beyond his vision. But then he saw Mahalak. She was due South, standing sentinel over the forest. The gravity of her majesty was too much for Choi, enfeebled as he was.

“If I’m to die lost in this land, perhaps I’ll do it at the foot of that tree. Maybe its roots reach the base of Mother Mountain and she can help me to Elidora,” Choi said to the wind, and struck South as best he could.

The boy limped towards the tree for two and a half days. He arrived to Mahalak in the early morning, approaching from a deep ravine, until he was suddenly upon the base of the mountain upon which the tree settled. Her aerial roots reached even the base of the ravine, like great stone serpents diving for creekwater over the cliff. Choi climbed the roots, struggling for footholds in the smooth wood pillars. His damp cloak weighed him down, but his spirit was pulled upwards, almost magnetically, towards the crown of the tree. With the help of his alpynstock hook, Choi grappled to the top of the roots. As he pulled himself onto relatively flat ground, Choi saw for the first time Mahalak’s central trunk, previously hidden from afar by the dense branches. The gray bark looked like the mountain itself had been molded and stretched like clay at the hands of a god. The many secondary trunks and horizontal roots reminded Choi of the childhood stories about the crumbled pillars in the ruins of Aotjar.

He flopped into a thicket of moss and fern, struck dumb by awe and exhaustion. Then Choi noticed the figs, hanging ripe and fat in numbers like stars in the night sky. Each fruit was bigger than his fist, and colored in a dark yet radiant purple. He devoured four. Juice and tears ran down his face. The gritty seeds and sticky flesh colonized the spaces in Choi’s teeth, while the sweetness wiped all other thought but pleasure from his mind.

***

A hoarse male voice cut through Choi’s revelation: “Well Master! Who is this hungry little man come to see us now?” But Choi saw no one.

“Quite a coat he has, a young warrior I bet! Or a poacher perhaps,” the raspy voice came again.

Choi looked frantically but only saw branches, leaves, fruit, and wasps. His mind was alight: the eyes had mouths after all, it seemed.

“Please show yourself! I mean no harm to the mistfolk” Choi managed, though he felt like he had a fig in his throat, and for a brain.

“Ahah hah! This one thinks that the mistfolk know the tongues of man. Definitely not from these parts…. He has the look of one of those High City scoundrels. Come to look for gold and medicines, hmm,” barked the man.

“Uhm, hello. I don’t know about gold or the forest folk. I’m not really here on purpose, but I do have a purpose. Where are you? My name is Choi O’Puyo. I live across the Spine but I am on an important mission that bids me to pass through this land. I saw this tree and had to see it closer.”

“Well okay then! A boy on a world-trodding mission to save us all, sounds about right. You’re lucky I’m not the skeptical type. Mahalak, though, I think, is wondering how you came about that pelt your wearing. Even she has met few with such a trophy.”

“I’ll answer your questions when you start answering mine. Are you the tree? Who is Malark?”

“Mahalak! Show respect in the presence of the divine, ignorant son. She has existed since before the first man came down the Mother Mountain, and will grow until the last man climbs back to Elidora. She is beyond man, let alone the comprehension of a little hobbledehoy like you. She is beyond time. Already her roots drink from the heart of the world and she is but a child of her kind; the seed of destruction of this world. And she will be its rebirth, when she and her own children devour the last rock. Beautiful, terrible, unstoppable…”

But that was too much for Choi in his state, and he collapsed into burning dreams of a monstrous tree grinding the world to dust and releasing vast fruits floating into the starry sky to seed new worlds. When he awoke, he was in a sort of room. It had three walls and a ceiling, but none of it was quite square. They were made of the living branches and roots of the tree, framing an incredible view of the misty forest below. Choi was laying in a bed of moss and saw robes and a few bizarre paintings hanging on the walls. Debidiah the Acolyte was sitting next to him with a worried look. His face radiated kindness through intense smile lines on his eyes and cheeks. Though he looked old, his coarse beard and curly locks were a deep black, almost purple. Choi noticed his eyes, skin, and teeth all had a faintly purple hue as well. He wore a simple tunic of loose gray felt. Leaning against his shoulder was a staff unlike any Choi had seen: it appeared to be made of living wood, with flowers and leaves of many types sprouting from the top and a healthy bundle of roots at the bottom that appeared to be slowing pulsing towards the ground.

“Ah, you’re awake. I’m sorry, friend. I’m not used to visitors. I got rather excited. Your leg is badly hurt and you’re quite undernourished. I hope you dont mind I brought you in here. It will be a good place to recover,” this time his voice was much gentler, though still gruff. Debidiah spoke little else as he served Choi a hearty meal of fresh figs, nuts, and honeywine before the traveler went back to sleep until the next day.

They spent the next week together as Choi healed. Much time was spent quietly sitting, crossed-legged, gazing into the shifting fogs. They grew to cherish each other's companionship: Choi had never met one so wise and Debidiah had never met one so intrepid. Choi told of his upbringing in Alpyn and his journey through the desert and across the Spine into the forest. He told of the High City and the town of Bones, of the wandering people, and of the strange republicans in the Southern range. He told of his grave message for the Lord King of the Flat Fief. Debidiah listened intently but his interest seemed mostly academic, in pursuit of a story itself, as if the wars and triumphs of man were of little consequence. He told Choi about old Djruits, the first people to come down Mother Mountain to Hyte. He spoke of their magic, more potent than that devised in even the most arcane caverns of the College of the Sages: how a man could warm himself in Winter with a thought, remember the lives of his grandfathers, reason with the birds, to take in energy from the sun and plants, and to grapple masterfully with fanged beasts. He said that such magic could not be written or studied, but only passed between living beings, and he demonstrated some of it. He slowly taught Choi how to navigate the Shrouded Forest by the feeling of the moisture in the air and in the lichens, and what to eat and not. Debidiah refused to speak of the mistfolk--saying that some things are better left as myth--but they would not interfere with his passage. He also spoke little of himself and his journey to forest, or of his duties to Mahalak.

Choi wanted to stay with Debidiah and learn the old magic, but he was compelled by duty to leave. One night under a full moon, Choi resolved to leave in the morning.

“Debidiah, this rest has healed my body and my spirit more rapidly than I could have believed. I will leave at first light. Will you come with me? You could share your message with the powerful Lords and with the College. Maybe we could bring the old magic back into the world. Maybe if man could become wise in the way of Djruits again, we wouldn’t need the great societies that go to war over trifles.”

The Acolyte smiled softly, “I never finished the story of Mahalak, if you recall when we first met. Did you know that in order for my master to produce a single fruit, a very particular kind of wasp must first fly into a blossom and die? Only through that act can a fig form, and thus the tree produces its offspring… and nourishment for the other insects, animals, and us. And only through this sacrifice are the habitats of the wasps created, or co-created. You can see them flying around now. They exist to die, as all things do, but the question is what they do with their singular life. Maybe an individual’s life is insignificant, or maybe it is of divine grandeur--who knows. I know, however, that life is allied. It is one big Life. Imagine very hard what it might be like to be that wasp…maybe you can understand the calling of the fig blossom. Now, try to imagine what it might be like to be a tree. Don’t worry, it took me many years to do that. It’s hard. But now, imagine you are a rock or a drop of water. I promise, no matter how hard you cannot.”

“Because a rock is dead? Choi interjected.

“Ah, but to be dead is to be a part of the living world, no? No, a rock is but a manifestation of the void. A rock’s greatest purpose is that it might be brought into the world of living things, perhaps I eat it, or it gets pulverized into soil to grow a tree. This is the great struggle between the animate world and thoughtless, cold nothingness. They each seek at all times to destroy the other, to make the re-universe in its own way. I knew which side I was on long ago when I was a young man from the High City, gone to the College to employ myself with their so-called wisdom. I was sent to the Shrouded Forest to collect specimens, but I had no plans to return. I had read tales of the tree-god, of Mahalak, to whom the wise Djruits of old would pay homage and whose bones are now dust in these figs. And I found her; the true master of Life in all her majesty. None are more redoubtable than Mahalak in the oldest magic there is: bringing the unchanging, unliving into the changing, the living.”

Choi felt blood rushing into his face. “What about humanity? We have spread over the entire continent and are the most intelligent life forms?” We are your kin and need your help. This is just one creature, as mighty as she may be.”

“You don’t understand, my boy, that it makes little difference whether one has flesh or bark, just as beak or hoof are of little consequence. A man might raise an army, but can be beckon a wasp into his mouth? Can he live on sunshine and water, or fly? I don’t think man is quite as smart as we like to think. We have steered ourselves towards decay, unwitting agents of the void. No other being wastes, or hates, or kills mindlessly. And we should not forget that only women can create life, and even so they have lost the respect of men in the cities. Choi, my place is with Mahalak, she who will be the last, the champion of Life. Someday, she will defeat the void and consume this world, unless man destroys her in her infancy. And then the cycle may repeat or seed new worlds; we cannot know what happens at the end of all things… She may take the lives of wasps, but she gives fruit and so much more. I am a wasp. I will die here, in a way at least. Let us leave it at that, young friend. Maybe you’ll come back and we can talk again, or maybe I will be a fig by then.”

And so they sat. In the moonlight, Choi watched the swirling mists and watched the fate of the world unfold. At first light, Choi left to make his way towards the Lord King in Ornal, to complete his quest, though changed yet again. He brought with him a sack of figs, some to eat, and--perhaps--some to plant along the way.